Field Report:

After hours at

the Beach

For what unnatural delights

do we rot our natural lives?

Aparri Beach, Cagayan. 2004

When I was five, I encountered my first beach: the black sands of Appari. Its rocky shores were far from the postcard ideal– in truth it was an estuary, the border between a riverbed and an ocean, bursting with life. Even as an attempt at a tourist-y escape the damp grass and greenery boldly contrasted the site’s branding. There the freshwater fish and the saltwater fish meet to mingle and the sea crabs and mud crabs show off their shells. My grandparents had been greatly amused by my attempts to eat the sand, the taste was that of mineral-rich soil without a hint of saltiness yet despite my daring I couldn’t manage to swallow it..

The Aparri beach I once knew is no more, lost to black sand mining.

One weekend, a month after my Aparri trip, my family opted to visit Rizal park and stroll through the entirety of Manila Bay walk. As a small toddler, I was enchanted by the street lights that looked like dazzling colorful orbs and the giant Coca-cola statue. But what called to my young mind was the Bay itself, its waves seemingly beckoning me to it. I asked my Tita Cecil if it was okay to take a dip (even pulling my shirt up, assuming she had brought a bathing suit for me) but she held my wrist tightly and pulled me aside.

“No bunso, it's dirty there,” she said sternly, “There’s nothing alive in that bay anymore. If you swim there, you’ll die.”

Manila Baywalk. 2005

The foul smell hitting my nose convinced me to turn away, but I didn’t believe her entirely. There were still seagulls swooping down into the water, and if anything was going to die, they would probably die first.

In response to the fetid, garbage ridden shores, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources undertook a project of beach nourishment and beautification. They achieved this by laying down about 3,500 metric tons of crushed dolomite from the quarries of Alcoy, Cebu in order to create a mirage of white sandy beaches.

Since I hadn’t been to a beach in three years, that mirage I could see from my apartment window drove me to a state of desperation and mania. In a haze, I dragged my equally beach sick girlfriend (born and raised in Subic Bay) all the way to Roxas Boulevard.

Manila Bay as seen from my apartment. Oct 20, 2025

Upon the descent down the walkway from the main road to the bay walk, I was immediately hit with a disgusting smell. It was much worse than when I was a toddler, as if it had festered and rotten over the years. A repugnant smell of fecal matter and urine heavy with ammonia, with a side of dead fish and wastewater chemicals mixed in for good measure. My girlfriend immediately noticed a sign from the DENR, in Tagalog, warning the public not to swim as the water does not qualify for “primary contact recreation.

Manila Baywalk Dolomite Beach, the filth, and the buildings that surround it. Oct 21, 2025

Stepping into the sand, our sandals crunched into the dolomite. The mix of gravel and coarse sand had yet to be weathered by the water, when my sandals slipped off my feet I yelped in shock and pain as if I had stepped on broken glass.

Littered all over the shore were pieces of garbage, whispers of the previous guests. Notably: a baby sized croc, weathered and worn. A sachet of shampoo and coffee, the head of a pineapple leftover from a picnic, bubble wrap pushed into a natural shape by the waves, a medicine bottle and the skin from a claimed lazada package.

The litter, as described

The scenery of garbage was interrupted when I was surprised by a bug that ran across my foot. We picked it up and observed it. It looked nothing like a sea flea, or any crustacean-like sea insects that usually populate white sandy beaches. Its wide body and small legs looked suited for shallower waters. Its striking appearance brought a memory back to me, a dengue awareness month activity I had to do when I was still in Muntinlupa Science High School. I made a presentation on the Water bug Diplonychus rusticus; which according to researcher Pio Javier of the University of the Philippines Los Baños’ College of Agriculture, could be the solution to the Philippine’s dengue problem as it eats 86-99 full grown mosquito larvae per day.

Bug from dolomite beach on styrofoam (left) compared to Diplonychus rusticus specimen surrounded by dead mosquitos (right)

It took me a while to identify this bug (despite my strong memory of it) because these insects aren't found on beaches. They thrive in shallow stillwater where mosquito larvae are abundant and readily available to them. Since the waves lapping on the shore wouldn’t be a laying ground for mosquitos, I looked further inland into the muddy flood waters across Roxas Boulevard, where the water bug had been headed before I interrupted it. Gently, I laid him back down from the styrofoam I picked him up with and sent him on his way.

That was when I noticed a small sprout peeking through the gravel, seed pod still resting next to it. The pod looked hollow and woody, the seedling slightly curled at the tip as if unfurling. I looked up at the gate of the beach where a young talisay tree was planted on a pot. Understandably so, as talisay is an endemic tree that can survive the air index of a polluted metropolitan area. But since their seeds are dispersed through Hydrocony (water dispersal) water must have flowed from the street to the bay. This indicates that runoff from the city is polluting the bay and accelerating coastal erosion on the dolomite beach.

Seedling and pod found on Dolomite beach(left) compared to Talisay Seedling about to unfurl(top right)

and Talisay seeds next to seed pod husks(bottom right)

A 1647 plate of Manila Bay published by the Dutch East India Company. Large European square-rigged ships are at anchor. From the book Treasures of the San Diego (1997).

Though the shore was surrounded by potted endemic plants, there weren’t any shrubs growing in the water. I had expected a “rehabilitation project” to actually rehabilitate the water to what it should be. In Manila’s case, a mangrove forest. Back then of course, there was never any dolomite there, nor was there ever a beach.

It was said that Manila was once covered in Scyphiphora hydrophyllacea, otherwise known as “Yamstick Mangrove” or “Nilad”, a mangrove shrub that grew around the coastlines of Manila bay. It is even said that the city’s name Manila came from a misunderstanding between a native and a Spaniard, the native refers to the area as “sa may Nilad” which the Spaniard interprets as “sa Maynilad.”

This Spaniard, of course, was looking to acquire these flowers as this story most likely was set in the middle of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade that solidified Manila as the capital of the Philippines.

As early as 1647, Manila was established as the main hub for trade and commerce in the Philippines. This meant that it was one of the first places in the country to get urbanized. Many people from provincial areas flocked to the city for more work opportunities, and with the rapid growth of population, more and more land was cleared around this area to make space for the people. And as roads and buildings were established along the coastline, this spelled the decline of the Nilad plants and other mangroves.

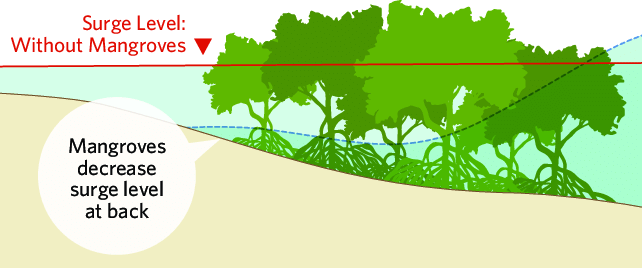

Graphic By Siddharth Narayan for his study "Valuing the Flood Risk Reduction Benefits of Florida's Mangroves" thats shows how magroves protect coastal areas from flooding when sealevels rise due to heavy rainfall or earthquakes

Though this move might make sense from the perspective of economic growth, the long term side effects of losing mangrove forests lead to vulnerabilities in coastal areas in which they no longer have a barrier that protects them from sea surges when the tide becomes higher due to natural disasters, leaving them at risk for flooding.

Even worse than destroying the endemic mangrove population around Manila’s coastlines is completely covering the natural deposits of Hydrosol soil that hold water with Dolomite, a loose sandy soil not found in shores but mined from a mountain. With this mountain soil being dumped into Manila bay’s coastline, whatever creatures were living in the loamy natural soil have died. The Dolomite also lowers the oxygen levels in the water and ultimately acts as much as a pollutant as plastic garbage does, as it does not belong in the coastline.

Though we found life grappling for purchase on the roadside, we hadn’t any luck finding life within the brackish waters next to the beach. By the shore, a carcass of a fish seemed to mock my hope that life was still thriving in the coastal waves. My girlfriend and I check the corpse, contemplating the possibility of it being a remnant of a visitor’s picnic, like the case of the pineapple head. To our disappointment, the fish appeared to be a Scatophagus argus, otherwise known as the spotted scat, a fish native to Manila bay. Not the type of a fish you’d see in a picnic.

Fish from Dolomite beach(left) compared to Scatophagus argus specimen (right)

Perhaps now Manila Bay is truly dead. Contrasting to my childhood, the seabirds swooping to feast on fish were eerily absent. Only a single gull feather whispers a possibility, yet that could be explained by it being displaced by the water.

A coastguard calls out that the beach is closing soon– at sunset, in fact. The orange haze of the sun was bleeding through the horizon already, and soon it would be quite dark. We make the trudge back, trying to out pace the dying light.

A single gull flies by.

As the nightlife of Manila wakes up, so do the fish of Manila bay. The turbulent waters take on the quality of opalescent TV static as their writhing bodies– either in an eating or breeding frenzy– stir up the water. Occasionally a singular fish or an entire school breaks through the surface, leaving echoing ripples and the resounding woosh and thwack of their bodies leaving and hitting the surface.

A school of fish leaping at Manila Baywalk Dolomite Beach. Oct 21, 2025